India’s agriculture industry is at a crossroads. When India became an independent nation 75 years ago, agriculture was the driver of the economy, contributing more than half of the nation’s GDP. Today, India is still one of the world’s largest and most diversified food producers, and agriculture—the source of more than 20 percent of India’s income—remains a central part of the economy.

But there are significant problems holding back the nation’s untapped potential. If solved, a flourishing agriculture industry could both boost the economy and significantly improve farmer livelihoods and income. By 2030, agriculture could contribute around $600 billion1 to India’s GDP—an increase of 50 percent over its contribution in 2020. But to get there, India must unlock growth and productivity for the sector.

The key to expanding India’s transformation into a farming powerhouse is agricultural technology, or agtech. India lags behind developed farming nations in agtech. Simply put, India’s farmers are competing at a disadvantage: half lack basic farming equipment, three of every four farms are at risk of crop damage from pests and weather, and 50 percent of India’s farmers lack access to traditional financing sources. Those who can get credit often pay inflated interest of 10 to 25 percent above market rates.

In this article, we examine agtech’s potential, how it is already improving outcomes, and what investors are looking for as rural India embraces modern farming. Agtech can be a shot in the arm for India’s farmers, making them more profitable and boosting the contribution of agriculture to India’s economy.

Historically, the farmer was just one of the many stakeholders involved in a market that centered on mandis—the local markets where farmers sell their products at auction. The advent of digital technologies and the evolution of multiple agtechs have put the farmer right at the heart of the entire ecosystem. Solutions have begun to be more farmer-centric: each part of the value chain that is digitizing, be it finance, inputs (products needed to grow crops such as seeds, agrochemicals, and fertilizers), or advisory—are directly targeting the farmer.

Agtech is already boosting Indian agriculture

Between 2013 and 2020, the agtech landscape in India grew from less than 50 start-ups to more than 1,000, fueled by increased farmer awareness, rising internet penetration in rural India, and the need for greater efficiency in the agriculture sector. Moreover, India’s regulatory environment is gradually evolving to facilitate the growth of digital technologies in agriculture.

Agtech in India continues to ramp up—from core companies in the value chain using digital technologies like “super apps” to innovations by start-ups, or “agrifintechs,” and large technology companies.

Existing agriculture incumbents use digital technologies to either go direct to the farmer or to expand products and services across adjacencies. Suppliers are becoming buyers, advisers are adding finance—any combination is possible and happening:

Providers of farming supplies such as agrochemicals, fertilizers, and seeds are using technology to create direct-to-farmer sales channels that bypass middlemen and retailers. For example, UPL (traditionally a core agrochemicals player) is providing mechanization services and agrochemicals to farmers through its nurture.farm digital platform. The company has also expanded to provide financing, advisory, and market services.

Firms, including banks and nonbanks, primarily engaged in providing finance through farm and rural loans, are using technology to better understand the farmer, provide targeted products, and reduce loan risks. For example, the State Bank of India (SBI) developed the YONO Krishi app to meet farmers’ finance, inputs, and advisory needs.

Companies that sell farm equipment have also started providing mechanization as a service to farmers. Mahindra, for example, offers a tractor rental service.

Firms that operate in procurement, processing, or the selling of agricultural products have started to integrate backward into the supply chain and create market linkages for the farmer. For example, ITC, a core outputs player, used its e-Choupal network to expand direct-from-farm procurement over the past 20 years. It has now launched the ITCMAARS super app. Using a partnership approach, the app gives farmers access to modern tools, quality inputs at the right prices, and finance.

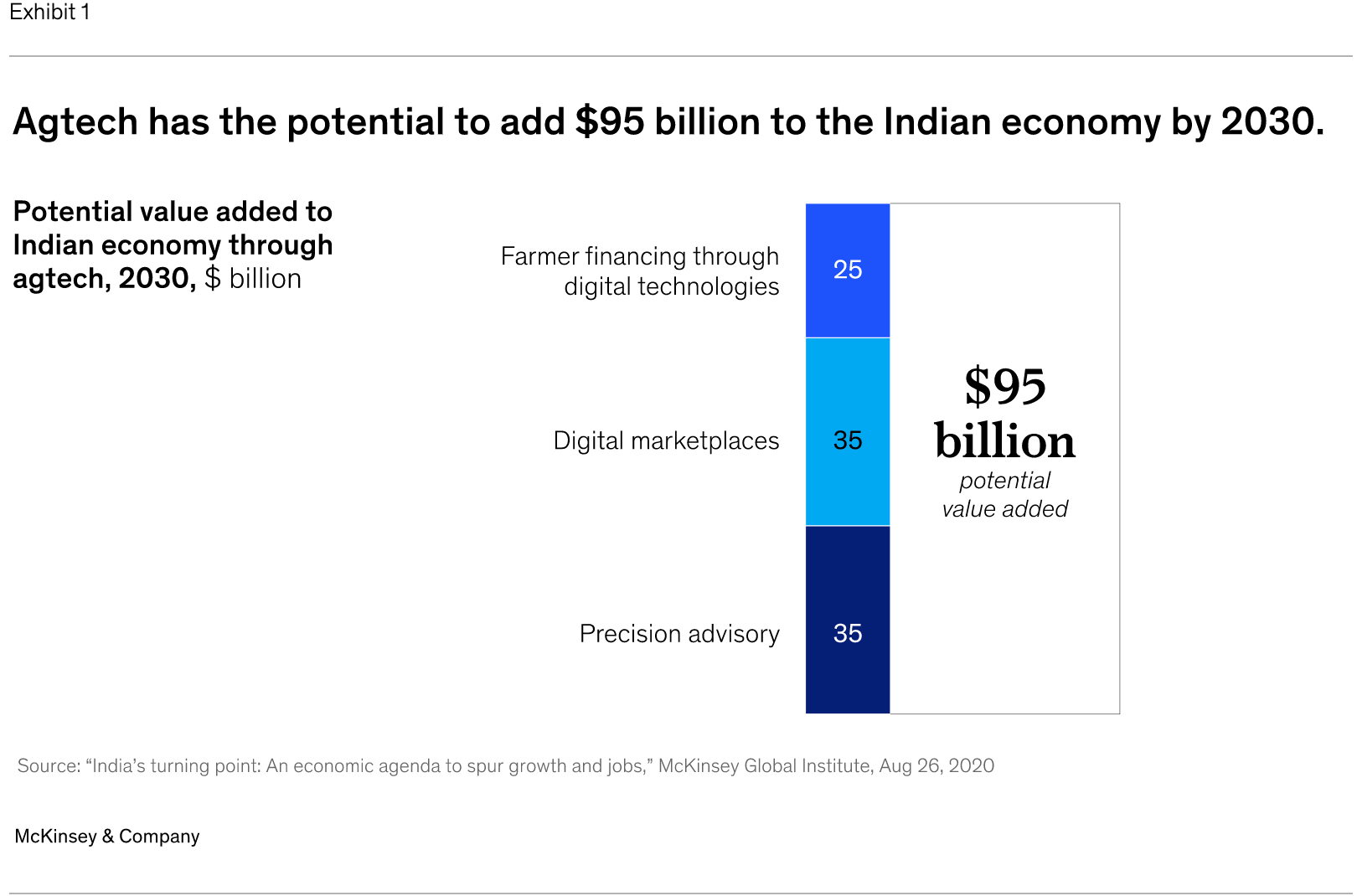

Fully nurtured, the agtech ecosystem has the potential to propel Indian farmers’ incomes to grow by 25 to 35 percent , and add $95 billion to the Indian economy, through reduction of input costs, enhanced productivity and price realization, cheaper credit, and alternative incomes (Exhibit 1).

The government’s role in enabling agtech

India’s government has also taken several policy steps and conducted pilots to foster technology and innovation in the agricultural sector:

Easier digital reach through farmer collectivization. The government has promoted farmer–producer organizations (FPOs), granting $750 million to set up over 10,000 FPOs in the next five years. FPOs collectivize the otherwise fragmented farmer base, helping agtech companies (such as Samunnati) to easily access and scale up their business models.

Development of the “agristack.” India is creating a unified database of agricultural data sets, which will be linked to farmers based on their land holdings. This will enable agtech companies to customize offerings and products based on farmers’ needs, which vary by land size, crop sown, and soil conditions.

Digital soil-health cards. A digital soil-health-card program entails mapping soil composition and quality at the farmer level. It could help agtech companies in India to promote precision-farming initiatives and tailor offerings for specific farmer groups.

Digitally enabled direct benefit transfer in fertilizer sales. This initiative directly transfers subsidies for fertilizers and other goods to the farmer. It authenticates the farmer’s identity at points of sale and through verification. It could significantly encourage the adoption of fertilizers and reduce leakages in transportation, maintaining affordability for smallholder farmers.

National Agriculture Market (eNAM). This pan-India electronic online trading portal connects existing Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMC) mandis, forming a unified national market for agricultural commodities that ensures better prices for farmers through the transparent auction process.

Agricultural Accelerator Fund and digital public infrastructure. The government has recently announced a new fund for promoting the agtech ecosystem, potentially seeding new start-ups that may increase digital adoption and the range of digital solutions available to farmers. Additionally, the government announced its intent to build an open-source digital public infrastructure that will likely support agtechs with relevant information services across the value chain.

These initiatives are building an agtech ecosystem in the country, supporting farmers in areas where they need the most help.

What are investors looking for?

With government initiatives and the openness of farmers to tech adoption, agtechs are poised to engage with India’s farmers, but to be successful, they will need stable sources of funding and a vibrant, supportive ecosystem.

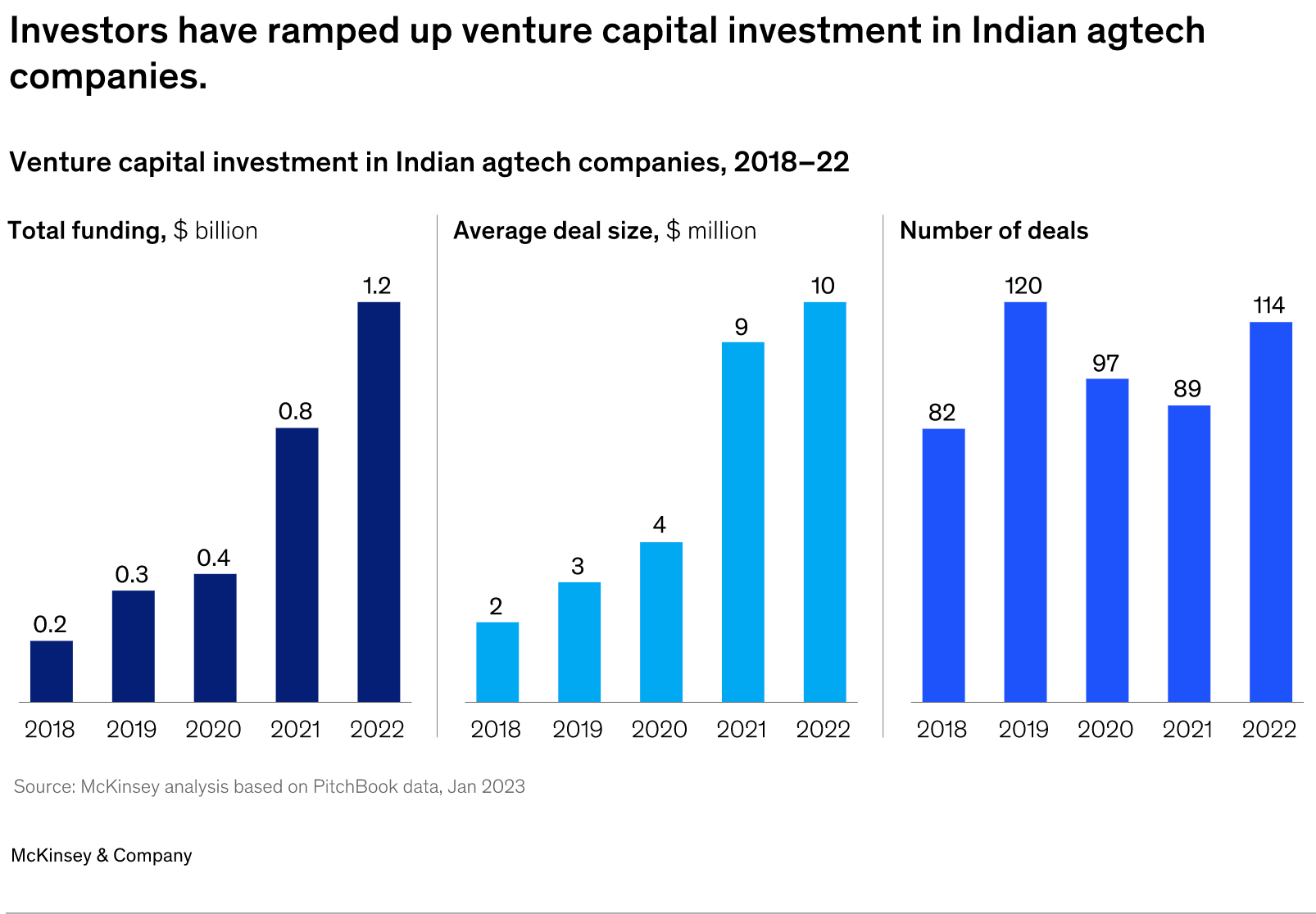

Agriculture technology in India has flourished with the growing attention from venture capital (VC) in recent years. Accel and Sequoia Capital invested in companies such as Samunnati, Ninjacart, DeHaat, and Bijak. During the past four years, agtechs in India have raised roughly $1.6 billion. VC firms invested more than $1.2 billion in 2022 alone through 114 deals, a 50 percent increase from 2021 and triple the investment made in 2020. The average deal size is growing, indicating that start-ups are maturing in this space despite an economic slowdown during the past two years (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2

Exhibit 3

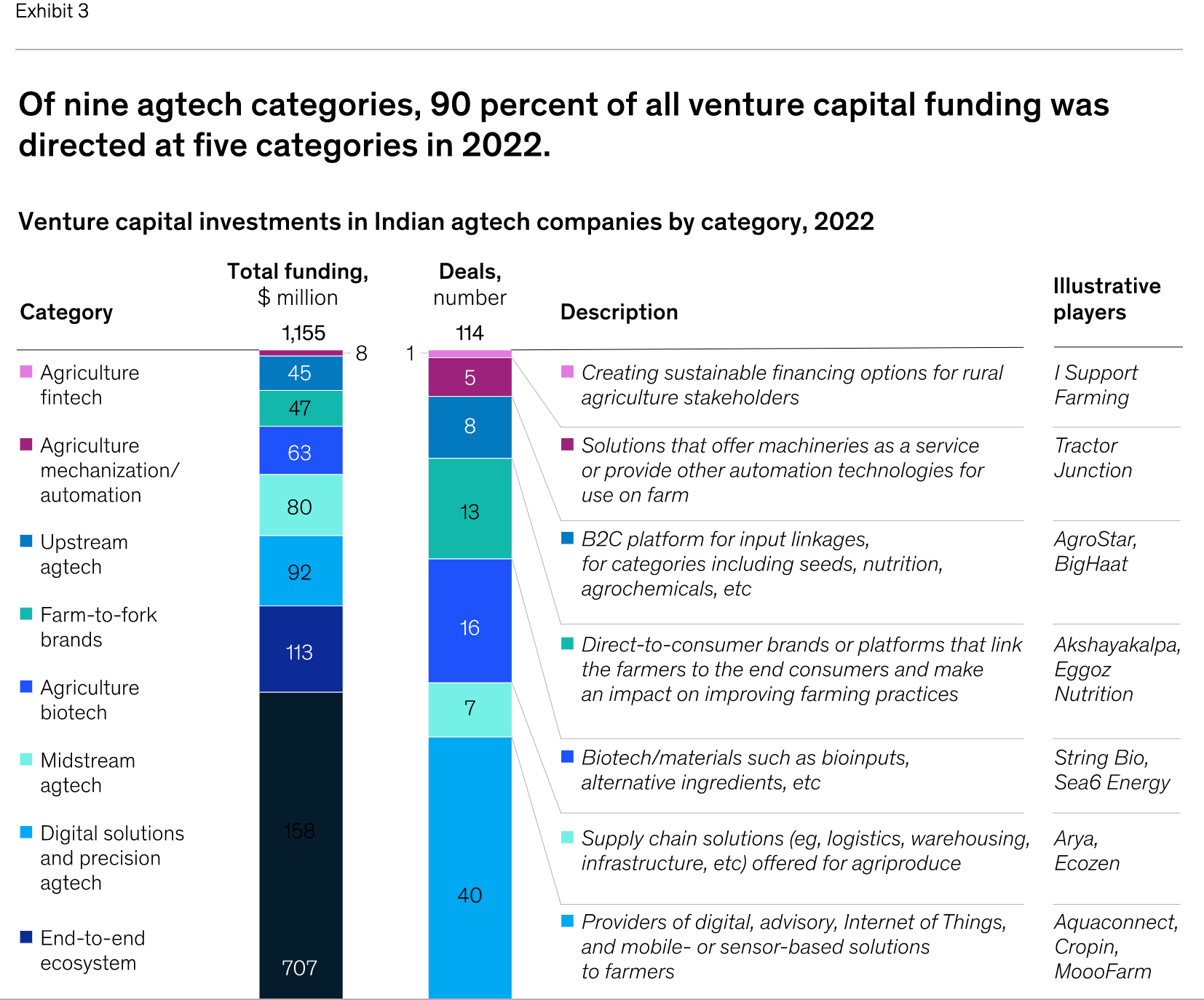

Downstream agtechs: These are primarily B2B or B2C platforms or brands to connect farmers with businesses or consumers. In 2022, such firms as Ninjacart, Absolute and Waycool raised more than $707 million in funding. Funding decisions are driven by the maturity of business models, the need for follow-up rounds of investments and highly accessible and monetizable opportunities across categories.

End-to-end ecosystems: These are platforms that play across the value chain and have a significant presence in multiple segments, such as inputs and outputs. In 2022, such firms, for example, DeHaat, attracted more than $113 million in funding.

Digital solutions and precision agtech: These are digital solutions or products which provide farmers with services such as advisory, precision farming and sensor-based solutions. In 2022, companies such as Cropin attracted more than $92 million in funding.

Midstream agtechs: These are agtechs that help provide supply chain solutions that improve efficiencies in areas such as logistics and warehousing. In 2022, firms such as Arya attracted more than $80 million in funding.

Agribiotech: These are agtechs that leverage biotechnology to create green and sustainable new products, or ingredients such as food additives. In 2022, firms like String Bio attracted more than $63 million in funding.

Unlike the rest of the world, where agricultural investment has centered on innovative foods—think Impossible Burgers or other plant-based foods—investment in India has centered on the basics: financing and technology to improve agriculture and farm practices and to avoid climate risks (such as droughts, pests, and flooding).

As a result, investors approach India with a different view. Our interviews with VC firms suggest that they focus on five factors when making decisions about new technologies: the size of the market, the breadth of offerings, traction with customers, an ability to scale, and the X factor (intangibles such as the learning curve it takes to use the new technologies efficiently).

Grow or die: Agtech success in India

Investors in Indian agtech are, or should be, asking some basic questions, including the following.

Does an agtech invest in multiple touchpoints and a breadth of offerings? Unlike e-commerce, agtechs get low transaction volumes for farmers but pay high acquisition costs, such as to get a farmer to install an app and try a product. This is complicated by the ceaseless efforts of multiple agtechs and incumbents to enter the space, lowering costs, and the farmers themselves being willing to experiment with multiple apps in the quest for most value.

To overcome this challenge, start-ups such as Gramophone, Samunnati, DeHaat, and more are offering more touchpoints and broadening their product portfolios to provide services across the value chain, from inputs and financing to advisory. Even platforms that start out with a single use case are expanding into adjacent parts of the value chain.

Does the agtech embrace a ‘phygital’ model? In rural India, both physical and digital infrastructure are important. Although 75 to 80 percent of farmer households have access to a smartphone, most still prefer to have physical touchpoints for digital support such as tutorials or help with app installation. Agtechs such as Agrostar and DeHaat have field teams to make on-ground visits and to drive campaigns for greater penetration of their apps.

One way to support a customer: the ITC e-Choupal ecosystem has managed to bridge the gap in rural digital infrastructure through a network of central sanchalaks (overseers), who act as physical touchpoints for the ecosystem and on whom farmers continue to rely.

In-person contact with the farmer can happen in multiple ways. Field representatives are one option. Other examples include a fertilizer supplier’s presence in India’s local micromarkets or rural bank branches for agrifintechs.

Is the agtech charging for the right product or service? The right monetization model is crucial. Some firms are trying to monetize advisory services, but most farmers—not just Indian farmers—are reluctant to pay for advice. In general, advice is a gateway to business, not a business itself.

Is the agtech light on assets? Agtechs that rely less on investments in assets can scale up across geographies quickly. For example, Agribazaar had reached $2,250 million of gross merchandise value in fiscal year 2021, with a fixed-asset base of around $2.5 million. It did so by shifting the responsibility of storage, quality checks, and transport to buyers and sellers on the platform for the majority of transactions.

Agtechs that require investments in physical infrastructure or assets typically try to keep their models dependent on local entrepreneurs who make the investments in equipment and facilities. For example, DeHaat and Agrostar use village entrepreneurs to provide last-mile service and deliveries within villages, enabling them to aggregate demand and deliver larger volumes.

The potential for a bumper crop Indian agriculture

The investors and agtechs that navigate India’s unique hurdles may see boundless potential. The next three to five years will be critical for incumbents and new players.

It likely won’t become a winner-takes-all market. A few major players, especially those with strong supply chain linkages to the farm, could emerge as dominant players in this space. These companies could support a host of smaller, niche players that will in turn leverage the end-to-end platforms for growth.

Collaboration will be crucial. While agtechs might facilitate better decision making and replace manual farming practices like spraying, reducing dependence on retailers and mandis, incumbents remain important in the new ecosystem for R&D and the supply of chemicals and fertilizers.

There are successful platforms already emerging that offer farmers an umbrella of products and services to address multiple, critical pain points. These one-stop shop agri-ecosystems are also creating a physical backbone/supply chain—which makes it easier for incumbents and start-ups to access the fragmented farmer base.

Agtechs have a unique opportunity to become ideal partners for companies seeking market access. In this scenario, existing agriculture companies are creating value for the farmer by having more efficient and cost-effective access to the farmer versus traditional manpower-intensive setups. It’s a system that builds: the more agtechs know the farmer, the better products they can develop.

India’s farms have been putting food on the table for India and the world for decades. Digital technologies could enhance production at every step, from high-quality agriculture inputs to world-class agriculture outputs. This could help create sustainable growth for the Indian farmer, boost economic fortunes in rural areas in a flourishing ecosystem, and benefit the entire economy

Source: Mckinsey.svg